How I built a sub-500ms latency voice agent from scratch

This post made it to the Hacker News front page! I'm genuinely grateful - and pleasantly surprised by the response. If you're building an AI or voice product and want hands-on help, I do focused consulting. Learn more.

I’ve spent the last six months working on a startup, building agent prototypes for one of the largest consumer packaged goods companies in the world. As part of that work, our team relied on off-the-shelf voice agent platforms to help the company operate more effectively. Though I can’t go into the business details, the technical takeaway was clear: voice agents are powerful, and there are brilliant off-the-shelf abstractions like Vapi and ElevenLabs that make spinning up voice agents a breeze. But: these abstractions also hide a surprising amount of complexity.

Just a few days before I started writing this, ElevenLabs raised one of the largest funding rounds in the space, and new frontier models like GPT-5.3 and Claude 4.6 dropped. This made me wonder: could I actually build the orchestration layer of a voice agent myself? Not just a toy experiment, but something that could have close to the same performance as an all-in-one platform like Vapi?

To my surprise, I could. It took ~a day and roughly $100 in API credits - and the result outperformed Vapi's equivalent setup by 2× on latency, achieving ~400ms end-to-end response times.

This essay walks through the full build: why voice agents are deceptively hard, how the turn-taking loop works, how I wired together STT, LLM, and TTS into a streaming pipeline, and how geography and model selection made the biggest difference. Along the way, you can listen to audio demos and play with interactive diagrams of the architecture.

Why voice agents are hard

Voice agents are a big step-change in complexity compared to agentic chat.

Text agents are relatively simple, because the end-user’s actions coordinate everything. The model produces text, the user reads it, types a reply, and hits “send.” That action defines the turn boundary. Nothing needs to happen until the user explicitly advances the flow.

Voice doesn’t work that way. The orchestration is continuous, real-time, and must carefully manage multiple models at once. At any moment, the system must decide: is the user speaking, or are they listening? And the transitions between those two states are where all the difficulty lives.

When the user starts speaking, the agent must immediately stop talking - cancel generation, cancel speech synthesis, flush any buffered audio. When the user stops speaking, the system must confidently decide that they’re done, and start responding with minimal delay. Get either wrong and the conversation feels broken.

This isn’t as simple as measuring loudness. Human speech includes pauses, hesitations, filler sounds, background noise, and non-verbal acknowledgements that shouldn’t interrupt the agent. Downstream from this are the things everyone notices: end-to-end latency, awkward silences, agents cutting you off, or talking over you.

We judge the quality of voice communication subconsciously, as it is so deeply ingrained in who we are. Small timing errors that would be acceptable in text - a pause here, a delay there - immediately feel wrong in speech.

In practice, a good voice agent is not about any single model. It’s an orchestration problem. You string together multiple components, and the quality of the experience depends almost entirely on how those pieces are coordinated in time.

The issue with all-in-one SDKs is that you get a long list of parameters to tune, without really understanding which ones matter or why. When something feels off, it's hard to know where the problem lives. That's what pushed me to go one layer deeper and build the core loop myself.

Starting out: the turn-taking loop

Before writing any code, I spent time iterating on the architecture with ChatGPT outside of my editor. I’ve found this useful when working in unfamiliar domains: build a mental model first, then implement.

My goal with agentic coding is always the same. I want to understand the structure of what I’m building well enough that I can open any file and immediately see why it exists and how it fits into the system.

After a few iterations, I reduced the entire problem to a single loop and a tiny state machine. At the core, a voice agent only needs to answer one question: is the user speaking, or listening?

There are two states:

- The user is speaking

- The user is listening

And two transitions where everything happens:

- When the user starts speaking, we must stop all agent audio and generation immediately.

- When the user stops speaking, we must start generating and streaming the agent response with as little latency as possible.

This turn-detection logic is the core of every voice system, so I decided to start there.

First pass: VAD and a pre-recorded response

For the first implementation, I deliberately avoided transcription, language models, and text-to-speech. I wanted the simplest checkpoint that still felt directionally like a voice agent.

The setup was minimal. A small FastAPI server handles an incoming WebSocket connection from Twilio, which streams base64-encoded μ-law audio packets at 8kHz in ~20ms frames. Each packet was decoded and fed into a Voice Activity Detection model - in my case, Silero VAD.

Silero is a tiny, open-source model (around 2MB) that can quickly determine whether a short chunk of audio contains speech. Turn-taking is a much harder problem than speech detection, but VAD is still a useful primitive, especially for deciding whether audio should be forwarded to more expensive downstream systems.

On top of this, I built a trivial state machine: a boolean flag representing whether the user was currently speaking or listening. When the system detected the end of speech, it played a pre-recorded WAV file back to the caller. When speech resumed, it sent a clear signal over the Twilio WebSocket to flush any buffered audio and stop playback immediately.

I started this way to isolate the hardest part of the problem - turn detection - without wiring up the rest of the system.

The result, while basic, was already impressive:

VAD-only test - the agent plays a pre-recorded clip whenever I stop talking, and cuts off instantly when I interrupt.

The agent responds immediately when I stop speaking, and shuts up the instant I interrupted it. Even without transcription or generation, the loop feels somewhat conversational.

This also gave me a useful baseline for latency. With eager turn-ending and a pre-recorded response, the system represented a lower bound on how fast a voice agent could possibly feel.

Where the VAD-only approach breaks down

This first pass was valuable, but its limitations were obvious.

Detecting the presence of speech is not the same as knowing when a user has finished their thought. A slow speaker might pause for several seconds mid-sentence. A pure VAD would eagerly decide the turn had ended and start talking too early.

In practice, real turn-taking requires combining low-level audio signals with higher-level semantic cues from the transcript itself. That meant the VAD-only approach couldn’t scale to a real system.

What it did give me was a clean control-flow model and a solid latency baseline to compare against. With that in place, it was time to wire in the full pipeline.

Second pass: flux and a real voice agent pipeline

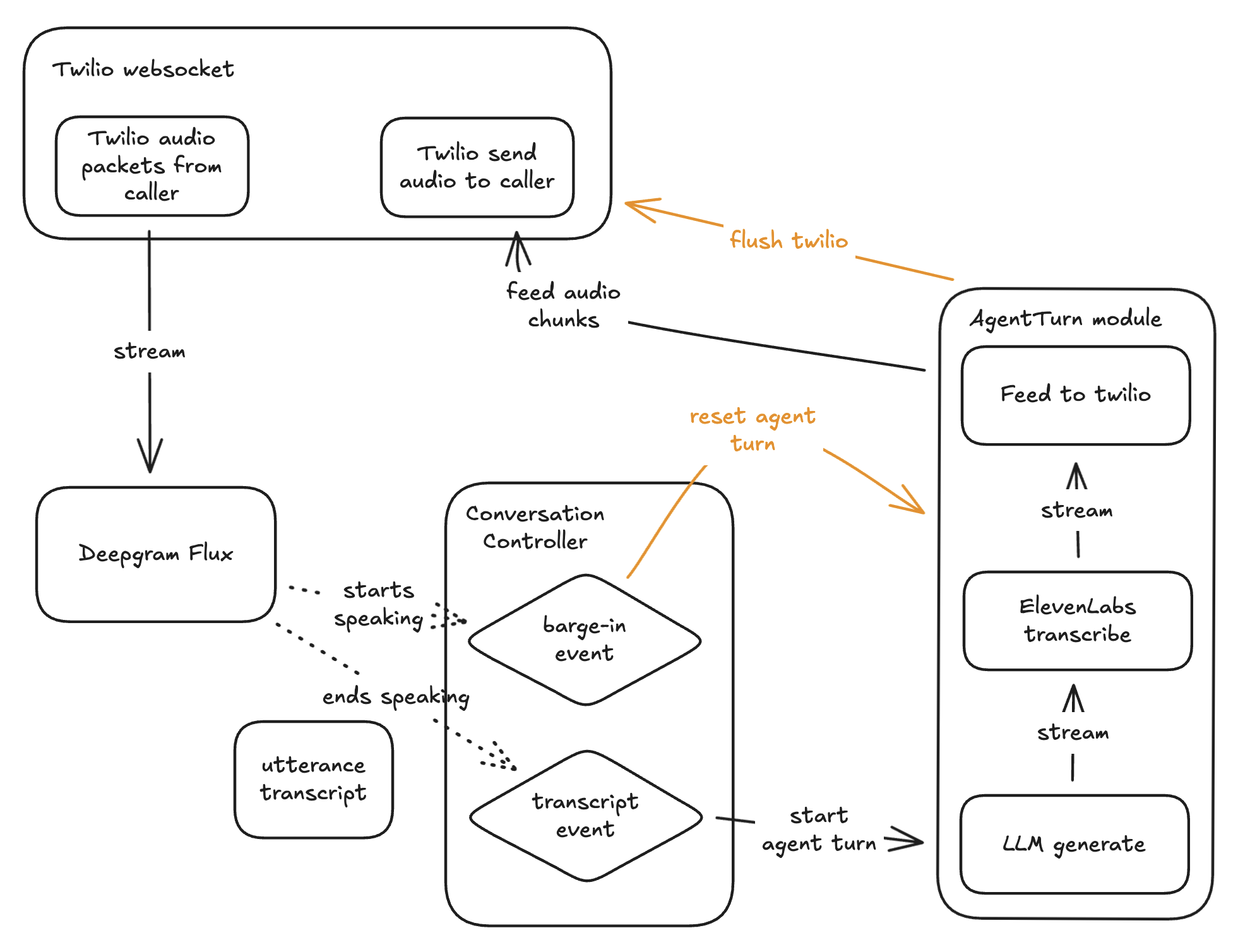

The next step was replacing my hand-rolled turn detection with something designed for production: Deepgram's Flux.

Flux is a streaming API that combines transcription and turn detection in a single model. You feed it a continuous audio stream, and it emits events - most importantly, “start of turn” and “end of turn,” with the final transcript included at the end.

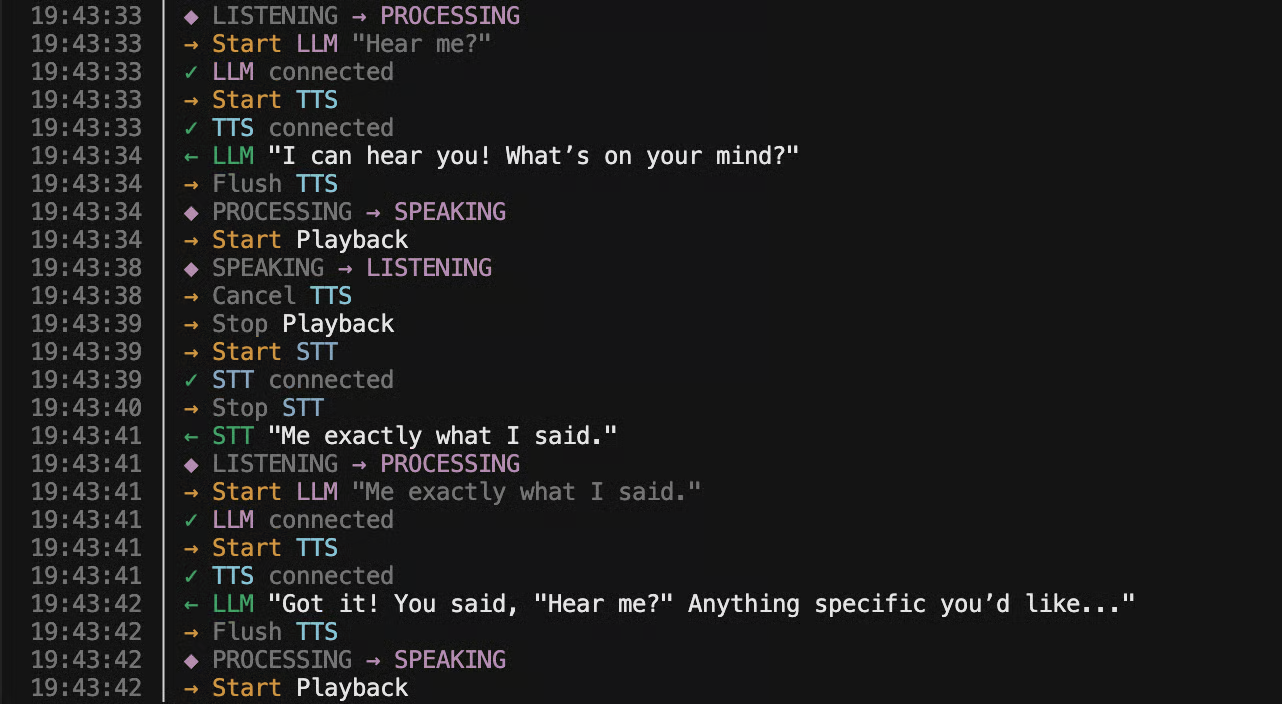

This replaced the core of my architecture. Flux became the source of truth for when the agent should speak and when it should immediately stop and listen.

On top of that, I built a dedicated agent-turn pipeline. When Flux signals the end of a user turn, this pipeline kicks off a real-time sequence:

- The transcript and conversation history are sent to an LLM to begin generation.

- As soon as the first token arrives, it is streamed into a text-to-speech service over WebSocket.

- Every audio packet produced by TTS is forwarded directly to the outbound Twilio socket.

The core idea is to pipeline every stream as to maximally reduce latency.

One important detail here was keeping text-to-speech connections warm. Establishing a fresh WebSocket to ElevenLabs adds a few hundred milliseconds of latency, so I kept a small pool of pre-connected sockets alive. That alone shaved roughly 300ms off the response time.

Barge-ins were handled symmetrically. When Flux detects that the user starts speaking, the agent pipeline is immediately cancelled: in-flight LLM generation is stopped, TTS is torn down, and a clear message is sent to Twilio to flush any queued audio. The agent falls silent instantly, and Flux resumes listening for the next end-of-turn.

The full architecture - Twilio streams audio to Deepgram Flux for turn detection, which triggers either a barge-in (cancel everything) or an agent turn (LLM → TTS → audio back to the caller).

Running it locally

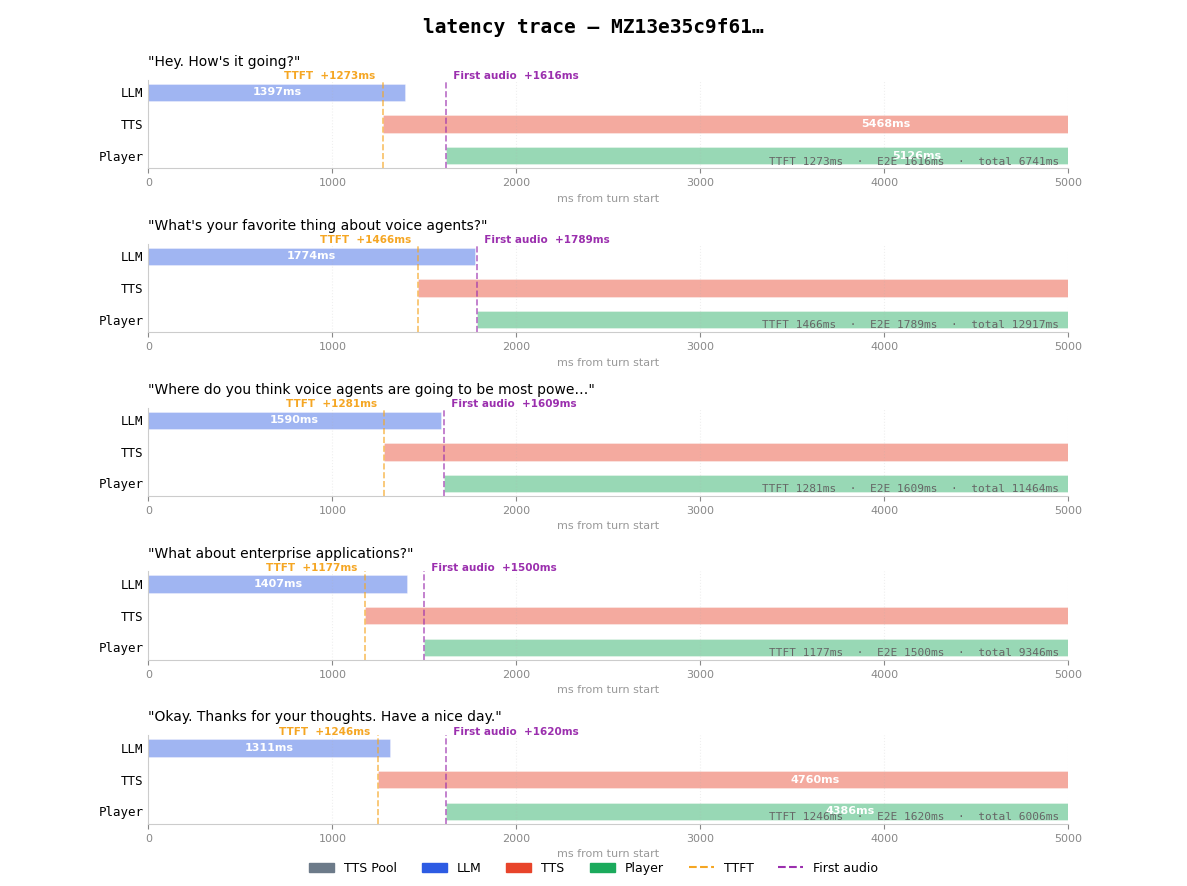

My first test was to run the orchestration entirely locally, mainly to understand how geographic placement affects latency. I built most of this project from a remote wooden cabin in southern Turkey, while traveling and hiking, so this setup was far from ideal.

Latency trace running locally from southern Turkey. TTFT averages ~1.3s, with first audio arriving ~1.6s after the turn ends.

End-to-end latency averaged around 1.6 seconds, measured from my server. According to Twilio, their media edge adds roughly ~100ms on top of that, bringing total perceived latency to about 1.7s.

That’s still quite far from Vapi’s ~840ms latency for a comparable configuration - more than twice as slow. At that point, the delay becomes noticeable. Conversations start to feel hesitant. Pauses stretch just long enough to feel awkward.

Full pipeline running locally - noticeable delay between each turn.

This was a useful reminder: even with a correct architecture, geography matters.

Deploying to production

In our architecture, every packet of audio hops to and from three external services. If you want to minimize latency, the orchestration layer needs to live physically close to them.

To further improve latency, I deployed the system on Railway in the EU region and configured Twilio, Deepgram, and ElevenLabs to use their EU deployments as well (Note: ElevenLabs automatically chooses the nearest region by default)

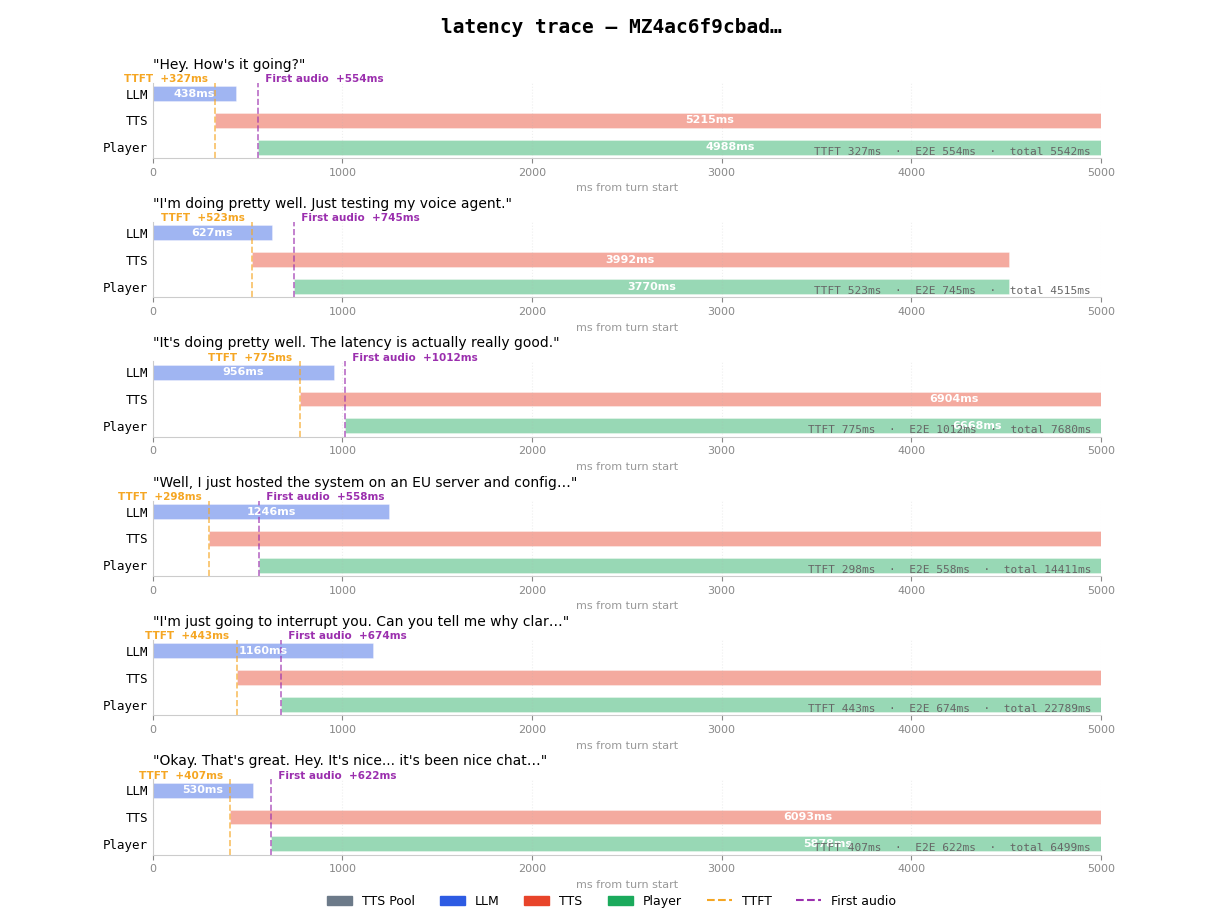

The difference was immediate:

Latency trace after deploying to Railway EU. TTFT drops to ~300-500ms, with first audio at ~550-750ms.

The average latency measured at the server dropped to ~690ms, which translates to a total end-to-end latency of roughly ~790ms once Twilio’s edge is included - more than 2x improvement!

For comparison, the equivalent configuration in Vapi - using the same STT, LLM, and TTS models - estimates around ~840ms. In this setup, the custom orchestration actually beats Vapi's own estimates by about 50ms.

More importantly, the subjective difference is obvious. The conversation feels responsive. Interruptions work cleanly. The agent no longer feels like it’s hesitating before every reply.

Hosted pipeline - the conversation feels natural, with clean interruptions and fast responses.

Model selection

So far in this project, I'd been using gpt-4o-mini, which seemed to be the lowest-latency model available from OpenAI. However, after digging a bit deeper, I discovered that the inference latency of Groq's llama-3.3-70b could be up to 3× faster.

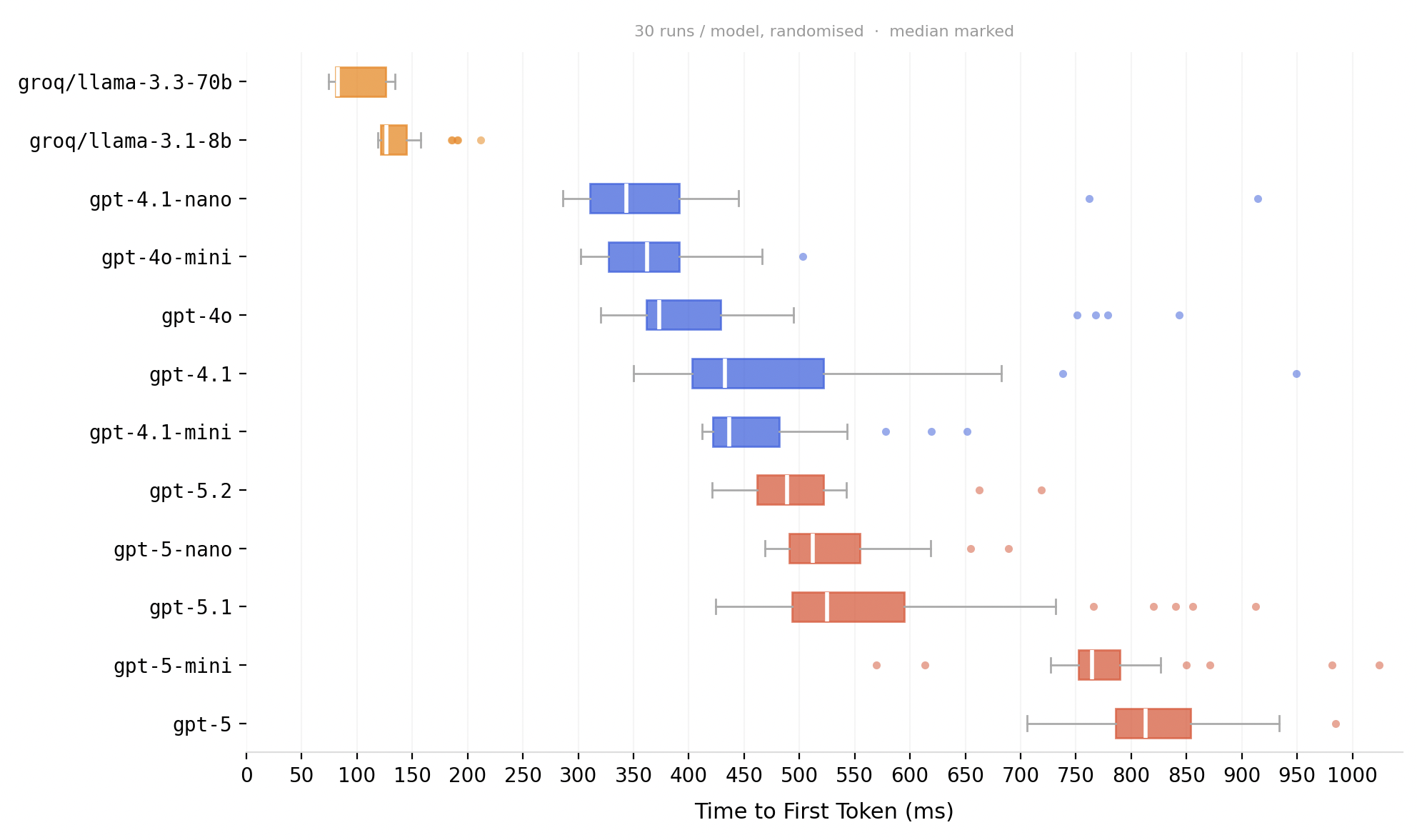

I wanted to verify this for myself, so I set up a small test harness on my production server. It ran 360 chat completions across a range of models, cancelling each request immediately after the first token was received. Below are the resulting first-token latency measurements:

First-token latency across providers - Groq's models are in a league of their own.

As you can see, Groq’s models leave everything from OpenAI in the dust. As far as I can tell, this is the lowest achievable latency without running your own inference infrastructure. It’s genuinely impressive - ~80ms is faster than a human blink, which is usually quoted at around 100ms.

I swapped out gpt-4o-mini for Groq’s llama-3.3-70b, and the results honestly surprised me:

Voice agent powered by Groq's llama-3.3-70b - responses arrive almost instantly.

Aside from the very first turn, the conversation felt smooth and snappy. With average end-to-end latency hovering around ~400ms, I was struggling to keep up - listening back to the recording, it sounds like I was taking longer to reply than the agent.

Latency trace with Groq - end-to-end latency averaging ~400ms, with first audio often arriving in under 500ms.

At this latency, interruption handling also feels dramatically better. The agent’s voice cuts out almost immediately after I start speaking, making the interaction feel far closer to a real conversation than anything I’d experienced before.

Technical Takeaways

I was really surprised that I could beat off-the-shelf providers by a full multiple. From extensive experience working with both Vapi and Elevenlabs agent SDKs on a real production use case, I found that my initial prototype is able to reliably achieve a 2x latency improvement, which is a huge deal when it comes to serving natural-sounding and pleasant voice agent interactions.

Building a voice agent from scratch taught me what actually matters in getting AI voice conversations to feel snappy:

Latency

What users experience as "responsiveness" is the time from when they stop speaking to when they hear the first syllable of the agent's response. That path runs through turn detection, transcription, LLM time-to-first-token, text-to-speech synthesis, outbound audio buffering, and network hops between all of them. You optimize this by identifying which stages sit on the critical path and making sure nothing blocks unnecessarily.

Model choice and TTFT

In voice systems, receiving the first LLM token is the moment the entire pipeline can begin moving. The TTFT accounts for more than half of the total latency, so choosing a latency-optimised inference setup like Groq made the biggest difference. Model size also seems to matter: larger models may be required for some complex use cases, but they also impose a latency cost that's very noticeable in conversational settings. The right model depends on the job, but TTFT is the metric that actually matters.

Pipelining the agent turn.

A production voice agent cannot be built as STT → LLM → TTS as three sequential steps. The agent turn must be a streaming pipeline: LLM tokens flow into TTS as soon as they arrive, and audio frames flow to the phone immediately. The goal is to never unnecessarily block generation. Anything that waits for a full response before moving on is wasting time.

Cancelling in-flight calls.

Interruption handling must propagate to all parts of the agent turn, immediately. When a user starts speaking, the system must cancel LLM generation, tear down TTS, and flush any buffered outbound audio simultaneously. Missing any one of those makes barge-ins feel broken.

Geography is a first-class design parameter.

Once you orchestrate multiple external services - telephony, STT, TTS, LLM - placement dominates everything. If those services aren't co-located, latency compounds quickly. Moving the orchestration layer and using the correct regional endpoints cut e2e latency in half. Service placement makes a huge difference.

Taken together, these lessons explain why voice feels deceptively hard. Real-time systems are unforgiving, and humans are extremely sensitive to timing errors.

Off-the-shelf vs. bespoke

This isn't an argument against platforms like Vapi or ElevenLabs. Those systems offer far more than orchestration: APIs, observability, reliability, and deep config options that would take real effort to reproduce. For most teams, rebuilding all of that would be a mistake - being able to test and validate a voice agent app without getting to this level of technical depth is truly amazing, and that's how I first got excited about the technology.

But building your voice agent yourself - even a stripped-down one - is still a worthwhile exercise. It forces you to understand what the parameters actually control, why certain defaults exist, and where the real bottlenecks live. That understanding makes you better at configuring the off-the-shelf platforms, and in some cases lets you build something more bespoke when your use case demands it.

Voice is an orchestration problem. Once you see the loop clearly, it becomes a solvable engineering problem.

The full source code is available on GitHub: github.com/NickTikhonov/shuo

Follow me on X for more.

Receive tasteful emails about my new essays and projects.

other essays: